Museum Exhibit Documents the Great Flood of 2016

|

“Charles Hatfield got a bum rap.”

With that assessment of the notorious rainmaker, local historian Dr. Steven Schoenherr launched into a review of the Great Flood of 1916 at the Friends’ annual meeting on January 27. The meeting preceded the 5:05 p.m. opening of an exhibit on the flood – exactly 100 years after heavy rains caused the Otay Dam to collapse – in the new Chula Vista Heritage Museum at the Civic Center library. Frustrated by a severe and prolonged drought, the City of San Diego had hired Hatfield, agreeing to pay $10,000 for his rainmaking expertise. Hatfield, who claimed he had successfully brought rain to other parts of the state, built a cloud-seeding platform near Lake Morena Dam and released chemical vapors into the atmosphere. |

During the business portion of the meeting, executive board president Shauna Stokes outlined the Friends’ accomplishments during the past year and goals for 2016. Mayor Mary Casillas Salas and library director Betty Waznis also spoke briefly. Michael Encarnacion was elected to a three-year term as vice president of the Friends’ executive board, and board secretary Nancy Lemke was elected treasurer.

|

Hatfield did not cause the flood, Schoenherr explained, but his efforts coincided with a complex weather system that brought rain all along the California and Baja coast. The first storm began on January 15 and lasted five days, flooding the Tijuana River and the Little Landers colony at San Ysidro. The second storm hit on January 26, and at 5:05 p.m. the following day, the Otay Dam collapsed, sending a wall of water down the Otay Valley, destroying homes, farms and businesses in its path to the bay.

Showing slides taken during and after the flood, Schoenherr, who is president of the South Bay Historical Society and the Friends’ Heritage Museum board, put the event in historical context. The population of San Diego County had nearly doubled between 1900 and 1910, and doubled again between 1910 and 1920. That growth was largely due to the completion of the Trans-Continental Railroad and the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. The San Diego-Panama Exposition of 1915 was a great success, drawing thousands of visitors from Canada and the East Coast, many of whom decided to stay.

At the time, the lemon industry in Chula Vista was a vital business, relying on the railway for shipping. The tent city in Coronado was very popular with locals and tourists, accessed by the railway around the bay. Visitors came by train to gamble at the racetrack John D. Spreckels had built in Tijuana. Excursion boating in the bay brought more tourists to the area.

Showing slides taken during and after the flood, Schoenherr, who is president of the South Bay Historical Society and the Friends’ Heritage Museum board, put the event in historical context. The population of San Diego County had nearly doubled between 1900 and 1910, and doubled again between 1910 and 1920. That growth was largely due to the completion of the Trans-Continental Railroad and the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914. The San Diego-Panama Exposition of 1915 was a great success, drawing thousands of visitors from Canada and the East Coast, many of whom decided to stay.

At the time, the lemon industry in Chula Vista was a vital business, relying on the railway for shipping. The tent city in Coronado was very popular with locals and tourists, accessed by the railway around the bay. Visitors came by train to gamble at the racetrack John D. Spreckels had built in Tijuana. Excursion boating in the bay brought more tourists to the area.

Water for a Booming Community

|

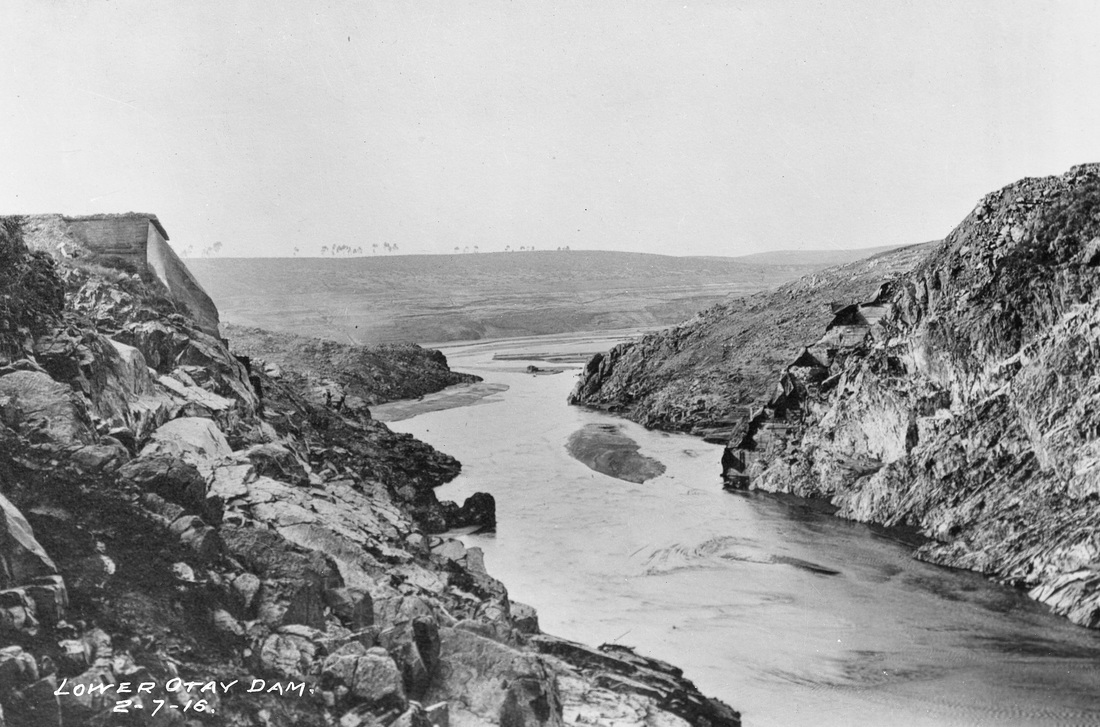

The Lower Otay Dam was completely destroyed as shown in this photo from February 1916.

|

The county had very few reservoirs and dams, and local leaders wanted to keep them full to provide sufficient water for the booming population. The Lower Otay Dam, built in 1897 across Otay Canyon, was made of dirt reinforced with cement and metal plates. Already full when the rains began, the dam was too weak to contain the water flowing down creeks and rivers from the back country. It was rebuilt in 1920.

The Sweetwater Dam, built in 1888, was 90 feet tall, the tallest masonry arched dam in the United States and a great tourist attraction, drawing visitors to walk on top of it. Although it did not break in 1916, water flowed over it and broke its abutments, causing flooding. After the flood, it was reinforced and public access was restricted. |

The Aftermath

The flood led to the end of many important industries in Chula Vista and the South Bay. The San Diego & Arizona railroad bridge washed out, along with much of the railway in South Bay, ending cross-country railroad service to the area. The lemon and packing industry in Chula Vista was devastated. So much silt and sediment was deposited in the bay that it became too shallow for boating. Streetcar service to Tijuana, Otay and Sweetwater Valley disappeared.

The original salt works, operated by the Western Salt Company, was destroyed but later rebuilt. The salt works was an important employer to the local Japanese community, who were contract workers there. Some of the Japanese in the South Bay moved north to San Diego and joined the albacore tuna fishing industry. At least 11 Japanese farmers in the Otay Valley lost their lives in the flood, and a memorial to them is located in Mount Hope Cemetery.

The Tijuana racetrack was destroyed and later rebuilt, but without access by rail. The Otay Baptist Church and the Otay Watch Factory were among the few buildings in Otay to survive. The black community of Woodlawn also survived the flood.

A reporter for the San Diego Union flew over the Otay Valley the day after the flood, and the resulting aerial photo was the first spot news of the disaster.

The original salt works, operated by the Western Salt Company, was destroyed but later rebuilt. The salt works was an important employer to the local Japanese community, who were contract workers there. Some of the Japanese in the South Bay moved north to San Diego and joined the albacore tuna fishing industry. At least 11 Japanese farmers in the Otay Valley lost their lives in the flood, and a memorial to them is located in Mount Hope Cemetery.

The Tijuana racetrack was destroyed and later rebuilt, but without access by rail. The Otay Baptist Church and the Otay Watch Factory were among the few buildings in Otay to survive. The black community of Woodlawn also survived the flood.

A reporter for the San Diego Union flew over the Otay Valley the day after the flood, and the resulting aerial photo was the first spot news of the disaster.

|

Army and Navy personnel were sent on expeditions to pick up those who were stranded, using the Otay School as a center for the relief effort. Members of the Chula Vista Yacht Club used their excursion boats for the rescue. Scavengers picked up salvage washed down the valley, including casks of wine from the Daneri Winery.

The flood was considered one of the 10 worst dam disasters in American history, causing $3 million in damage – about $65 million in today’s dollars. And Hatfield was never paid. The San Diego city attorney informed him that if he took credit for the rain, he would be liable for the damages. On the other hand, if he conceded that the flood was an act of God, he would not deserve his fee. Hatfield left town without his $10,000. |

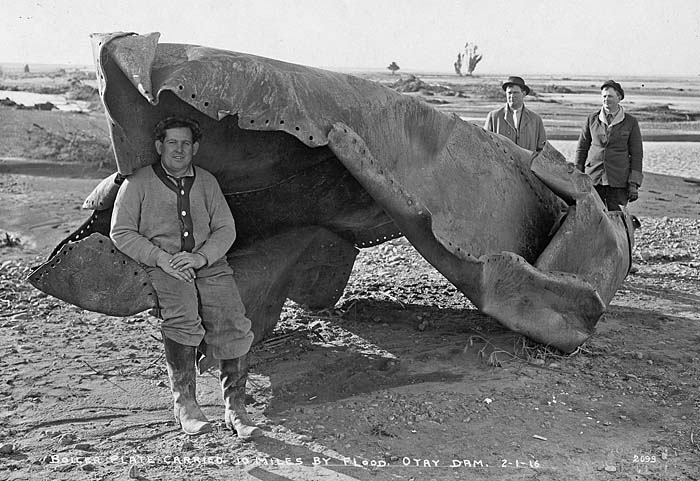

In this 1916 photo, Johnny LaPorte sits under a piece of what was once the Lower Otay Dam. He later became the first motorcycle policeman in National City.

|